There are only two reasons to go to Mahnomen: to gamble or to pay someone a visit.

Open, undeveloped land stretches out for miles on either side of Highway 59. The sky feels low and concave, a screen where a violet sunset and cirrus clouds parade. I pass corn field after corn field, a few farms where horses and cows graze. A “When in season” fruit stand, evidently not in season, sits boarded up in a front yard, and an “Eggs 4 Sale” sign is parked at the mouth of a driveway.

The phrase “food desert” does not sink in until your stomach starts to rumble in this town of 1,200 on the White Earth Reservation. Among the dining options in Mahnomen proper: the Shooting Star Casino, Burger Hut (closed for the season), and the Red Apple Cafe (which reduces its hours to breakfast and lunch during fall and winter).

I’m here to see Sean Sherman, founder of the Sioux Chef. He has scheduled a stop in northwestern Minnesota as part of his cookbook tour for The Sioux Chef’s Indigenous Kitchen, a collection of recipes based on the ingredients and traditions of Native Americans. The local library was too small, so his early-morning talk will take place at Mahnomen Elementary instead.

The lights of the Shooting Star Casino are the brightest in the town. Owned and operated by the White Earth Reservation Tribal Council, the venue houses 400 hotel rooms, a swimming pool, multiple restaurants and bars, live entertainment, and, of course, scores of betting tables and neon-faced games.

Police patrol the hallways and lobby between the hotel and casino. Young people in ill-fitting track pants, hoodies, and baseball caps loiter in leather chairs. A young woman pushes a stroller back and forth. Players stare blankly at twinkling slot machines.

I ask an employee where the restaurant is. “Which one?” he asks. The casino has five.

Mino Wiisini is a fast-casual cafe pretending to be healthy with green signage and an Ojibwe name that means “eat well.” At the counter, the menu board proffers a tray-by-tray tour of American junk food: pizza, burgers, and fries.

The fine-dining branch of the establishment, 2 One 8, comes with a ritzier menu that includes a pork Porterhouse and shrimp pesto linguine; there’s a barbecue joint that advertises all-you-can-eat boneless wings for Monday Night Football and Tot-Cho Tuesdays; and a Tim Horton’s storefront where glaze-drenched doughnuts gleam from the pastry cases beneath fluorescent lights.

I opt for Traditions, the buffet, a $12.99 all-you-can-eat affair, which despite the implication of its name is not remotely Native. Thursday is Steak Night, Friday is Seafood Night, and Saturday is Surf ’n’ Turf Night. Tonight, it’s a bought-in-bulk-and-reheated menu of broasted chicken thighs, pork roast, baked fish, taco bar, baked potatoes, mashed potatoes, scalloped potatoes, stuffing, alfredo pasta, breadsticks, egg rolls, and “chef’s choice.” Tonight, the chef has chosen meatballs.

The diners here are primarily senior citizens, many of them overweight and most of them white, with a few younger Native Americans. Neil Young’s “Harvest Moon” echoes through the room, as does someone’s phlegmy cough. A pair of men wearing stained jeans, drilling company shirts, and knit hats wolf down an end-of-shift meal.

No one seems to be enjoying their food.

Flour, Lard, Salt, Sugar

“Welcome to our world,” says Dana Thompson with a pat on the arm as we converge in the gymnasium of Mahnomen Elementary the next morning. Thompson is Sean Sherman’s business and life partner. The blue-eyed blonde dutifully lugs cookbooks, a thermos, and a shoulder bag, her long earrings swaying back and forth.

“There are not options,” she says of the local food scene. “Literally the only even remotely healthy option is Subway, and it’s hard to get away from gluten that way.” Not that it hinders her diet. As she admits: “I eat everything. I’m a big eater. I eat like seven times a day. But Sean is trying to live clean right now, eliminating dairy and gluten and pork and stuff.”

In preparation for the trip to Mahnomen, they packed a cooler with indigenous foods, what Thompson describes as “nuts and berries, and stuff that you get at the Wedge [Co-op] that you take for granted.”

Though they’ve been running ragged—Crookston last night, Mahnomen today, Moorhead and Bemidji later this week—Sherman especially seems to take the stress in stride. He smiles often, laughs easily. He snacks on something brown and chewy.

As Sherman sets up, Thompson snaps pics of him with her cell phone, documenting their work for city slickers back home. “We don’t want to contribute to poverty porn,” she says, “we just want to raise awareness that this is a thing and it’s super real.”

Finally, about 60 kids filter in and take seats in the bleachers. Over 80 percent of the students here are Native.

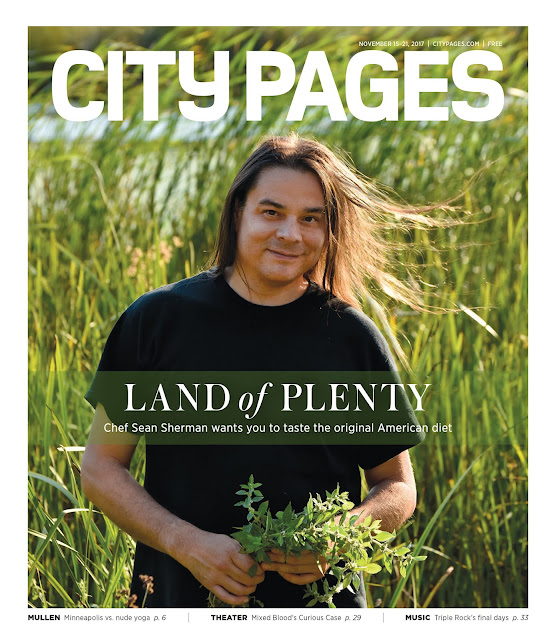

Sherman, dressed in a black T-shirt, baggy blue jeans, and worn brown boots, with his long black hair pulled back into a ponytail, takes the mic. He tells the young audience that he grew up on Pine Ridge Reservation in South Dakota. He clicks a button and shows a slide of commodity food, the packaged products of his childhood. “This is what the government gives Native American reservations. You can live off them, but if that’s all you’re eating, you’re not getting the right kind of nutrition,” he says.

He explains that the Sioux Chef wants to revive the indigenous diet of nuts, berries, wild rice, maple, rabbit, duck, goose, bison, venison, turkey, quail, walleye, and trout—what he calls “pre-contact” foods—while excluding dairy, wheat flour, processed sugar, beef, pork, and chicken.

There are 567 Native tribes and 2.9 million Native people in the U.S., Sherman says, yet Native restaurants are nonexistent on the culinary landscape.

“Everybody in America should understand that no matter where you are, there’s indigenous foods there,” Sherman says. All around us are “free groceries,” he says, and every tribal community has unique regional fare. The problem is that we’ve become disconnected from these food systems. It’s imperative that we return to them, not only to preserve Native lifeways but to lower unemployment, be ecologically responsible, and improve health.

“Before Native Americans were removed from their traditional foods, they didn’t have things like high rates of obesity or Type II diabetes or even tooth decay,” he says.

He shows the kids a slide of the food he serves; plated, it’s modern art. Intimidating, even. “It all looks super fancy, but we’re just having fun with food. We’re just playing with all these cool flavors that have been here for a long time,” he says.

Sherman surveys the students. About one-third have picked berries. About a dozen have gone wild ricing and maple syruping. Most of them ice-fish.

During the Q&A portion of the presentation, hands shoot up. Kids ask about wild rice (it can be used to make flatbread, muffins, and even sorbet and tart shells). They ask about corn (yellow corn was “designed to have more kernels and higher sugar,” and is “less healthy than Native corn,” Sherman says). There are questions about bison, fishing, and hunting methods (bows and arrows, spears, trapping). One kid inquires about ramen noodles(“That’s in Japan,” Sherman responds). Another shares that he almost caught a rabbit (“They’re fast,” Sherman concedes). Someone asks if Sherman likes bananas. “I’m not a big fan of bananas. I don’t know why. I never was,” he responds. What about peas? another kid wants to know. “Yeah,” Sherman says, “they’re all good.”

And then, a loaded topic: fry bread. Sherman explains that he doesn’t make it because fry bread was born of government-given food staples: flour, lard, salt, sugar. “There wasn’t much people could do with that stuff because nobody had ovens. So the government showed them how to make simple foods like fried bread,” he says. “Fry bread became popular because it was part of the food staples that we had, but there’s no reason that fry bread should be considered Native.”

But the kids won’t let it go. One asks if there are different kinds of fry bread. “People put their own touch on it,” Sherman says, but adds, “Gluten is not very good for you.”

The last time Sherman came to White Earth, he spoke at the casino for 800 people; 80 percent were Native. Today, though the whole community was invited via backpack flyers and Facebook, only one Native parent showed up. Sherman is unsurprised. He posits that parents are working at this early hour.

Meredith McArthur is soft-spoken and bespectacled with black hair and dark eyes. She’s a member of White Earth and part of the American Indian Parent Advisory Committee. She volunteered to help sell cookbooks today. McArthur suffers from a wheat sensitivity, and one of her two children doesn’t eat dairy. The only Mahnomen restaurant she can eat in is 2 One 8, and that’s a splurge.

“I was like, ‘All right. Living in a smaller town, I have to start making a lot of my own food,’” she says.

Aimee Pederson, Indian education coordinator for all grades of the Mahnomen schools, says most people in town cook. “There’s not a whole lot of anything else.” She says many children eat thanks to the local Boys and Girls Club, which hosts meals after school and throughout the summer.

Though parents are absent today, there are a few other outsiders in attendance for Sherman’s talk. Donna Scholl is a teacher from Norman County West High School in Halstad, Minnesota, who brought half a dozen teens from her foods class for Sherman’s presentation.

“We’re beginning a unit on traditions, cultures, and religion,” Scholl says. I ask the students what food they’re eager to try; they’re as expressive as statues. Scholl answers: “I think we might try some wild rice recipes. I have a friend who’s Native and harvests wild rice herself and have several bags from her. It’s the real stuff. It should be fun.”

A gray-haired woman and a young man both have copies of Sherman’s cookbooks tucked under their arms. Dana McVeigh is a research assistant at the University of North Dakota. “I skipped out of all my meetings and classes to come over here,” she gushes. She cajoled her son, David, to bring her. She taught David to cook and they regularly swap recipes.

An archeology buff, Dana says she wants to “get back to the beginning” of food. David says he just wants to eat “what tastes good.”

A Lifetime of Work

Back at the casino, Sherman and I find seats in the empty pool area. As we discuss his unlikely career trajectory, he tosses handfuls of homemade trail mix into his mouth.

“For somebody growing up on Pine Ridge in the ’70s, I should have had no opportunity to get anywhere, statistically,” he says. Numbers would not have predicted he’d own a growing culinary empire and employ a team of 12, also set to expand.

Twenty years ago, Sherman, a member of the Oglala Lakota, left the Pine Ridge Reservation where he was raised and headed to Minneapolis. His intention was to enroll at Minneapolis College of Art and Design (MCAD), but he found his creative urges satisfied through the culinary arts instead. Kitchen work was plentiful, so he earned his chops in restaurants like Broder’s, W.A. Frost, and French Meadow, churning out chicken piccata and fettuccine alla bolognese. The Twin Cities served a wide array of global cuisine, but there weren’t any Native restaurants.

After too many 100-hour work weeks in kitchens, Sherman bought a one-way ticket to Mexico and shacked up in San Pancho to re-evaluate. An indigenous group there, the Huichol, sold goods on the beach every day. With their traditional dress and beadwork, they reminded Sherman of his roots. He was inspired to reconnect with the traditions of his ancestors.

After almost a year south of the border, he headed back to Minneapolis and began heavily researching indigenous agriculture; the processing, cooking, and preservation of Native foods; and the sources of salts, fats, and sugars his ancestors used. “I was really looking at it from a full culinary perspective. I wanted to understand all of it, all at once,” he says.

In 2014, he founded the Sioux Chef, a catering company in Minneapolis. As part of his work, he talked about indigenous food systems at conferences. “People were really warm and open to what I was talking about, and what my perspective was. I’d just run outside and gather a bunch of food and flavors and make it part of a meal.”

At one conference, members of Little Earth, a Native housing community on Cedar Avenue in Minneapolis, approached him about collaborating on an indigenous food truck. Tatanka Truck hit the streets in 2015. Word of mouth spread and national press followed. In 2016, when Sherman launched a Kickstarter to help fund the first indigenous restaurant in Minnesota, he blew past his goal, raising over $148,000.

This year, the Sioux Chef secured a partnership with the Minneapolis Park and Recreation Board and the Minneapolis Parks Foundation to open a restaurant at Water Works, a park pavilion in development in downtown Minneapolis. The restaurant will overlook the Stone Arch Bridge and St. Anthony Falls, a sacred place to the Dakota people, and is scheduled to open in 2019.

Sherman’s plans have expanded exponentially since his food-truck days. (“I accidentally created a lifetime’s worth of work,” he admits.) He recently founded a nonprofit, NATIFS (North American Traditional Indigenous Food Systems), the foundation of which will be a restaurant and a training center with classes on Native agriculture, cooking, food preservation, history, crafting, and medicinal foods, among other topics.

Sherman anticipates weekend sessions, weekday programs lasting a couple weeks, and apprenticeships for high school graduates. Trainees will take their newfound knowledge back to their tribal regions and design their own restaurants focused on their regional indigenous food. Tribes will name and own their restaurants; the nonprofit will oversee the sites for three to five years, until they prove sustainable. Eventually, this could grow into a network of Native restaurants that spans the U.S., Canada, and Mexico.

“We could try to go for a franchise model, but we don’t want to pull money from those regions,” Sherman says. “We want to push education, and food access, and economic opportunity outwards.”

I ask how difficult he anticipates this culinary revolution will be, given that food habits are near impossible to change.

“It’s going to be really hard,” he concedes. “Sure, you can go to Taco John’s. Or you can go to this really cool Native restaurant that’s particular to that area, and that’s using food right from that region, and it’s employing people, and paying for people to harvest stuff from that area.”

This kind of food sounds labor-intensive. Where, for example, is a chef going to get rabbit?

“We’re not telling everybody to eat only indigenous regional, we’re just wanting people to understand what that means,” Sherman says. “To see the diversity and understand how precious a lot of these Native pieces still are.”

“We’ve been sitting on top of this culture”

A week later, at the cookbook release party for Kickstarter supporters, Sherman addresses an assemblage of mostly white Minnesotans at Aster Cafe. The room is romantically lit and Sherman looks polished, with his hair tied in tight, shiny braids. He speaks for a few minutes, as does his co-author, Beth Dooley, an occasional City Pages freelancer. Dooley praises Sherman for making a cookbook with “so much integrity and so much love.”

Then it’s on to the food. Two long tables display gorgeously plated indigenous dishes. An array of colorful roasted vegetables—squash, beets, sunchokes, carrots, potatoes—prepared with sunflower oil and smoked salt are spread across wooden planks. Stone-ground corn chips serve to scoop up black bean dip and white bean dip with smoked white fish. Bite-sized wild rice cakes are stacked with either forest mushrooms and greens or sage smoked turkey and cranberry. Brown sunflower thumbprint cookies are filled with squash and mixed berries.

Lifelong Minnesotan Morgan Schultz and her husband are among those who supported Sherman’s Kickstarter campaign last year. “Every Valentine’s Day we try a new cuisine and we cook a big meal. We’ve done Syrian food, Japanese food, Szechuan, and Hunan. We’ve exhausted many regions. We’ve been wanting to try Native American food for a long time,” Schultz says.

Schultz says it breaks her heart that indigenous cuisine isn’t more prominent in the culinary space. “I am connected to it, and in a different way, it’s my heritage. It’s my geographic heritage. That’s not pretzels and lefse. It’s cedar and stuff that I don’t know how to use, yet, because I didn’t grow up with it,” she says. “Hearing Sean talk, this is so long overdue. We’ve been sitting on top of this culture.”

The following Saturday, Sherman, Dooley, and crew welcome a standing-room-only crowd in the Mill City Museum’s baking lab.

Though this event is billed as a cooking demonstration, Sherman sticks to his usual talking points about the decimation of Native food systems, the ubiquity of indigenous eats all around us, and how NATIFS hopes to revitalize seasonal, hyper-local cuisine. By way of example, he motions to countertop bowls of apples, cranberries, and chestnuts. He also holds up cedar branches. “You can’t get more Minnesotan than these foods,” he says.

The baking lab is not conducive to observation, and Sherman doesn’t narrate his process, so museum-goers will have to take his word for how simple he says his duck breast with cranberry sauce, corn meal, chestnuts, smoked salt, and rose hips is. The recipe takes a full 30 minutes for two professional chefs to prep; when it’s complete, Sherman holds the dish up for observation. It’s the kind of cuisine Sherman is becoming known for, bright and beautiful. But how practical?

Compare prices at Lunds & Byerly’s, where duck breast costs $1.33 an ounce and chicken breast costs 33 cents an ounce. That might not seem like a big difference until you’re feeding a family. (And there are several large families at Sherman’s talk today.) Duck is a luxury, not a daily staple.

By the time the recipe is complete, half of the audience—and all of the large families—have left.

“You really can do this at home,” says Dooley, a small but sturdy woman with wavy gray hair and a cheerful demeanor. “The only tools you really need are your two hands.”

Dooley discusses the “astounding flavor” of dry meats and the nutritional properties of wild rice, and shares an entertaining anecdote about the recipe-testing stage of the cookbook, when she realized she forgot to purchase juniper at the co-op. Sherman, perplexed, pointed out that she had juniper in her front yard. “I didn’t realize how much food I’ve been walking over,” she says now. The crowd laughs.

“There’s so much wisdom in these ancient methods,” Dooley says.

“Everything has a purpose if you take the time to learn it,” Sherman echoes.

One young woman with a curtain of golden hair and a red backpack populated with buttons seems particularly engaged, and is first in line to buy a cookbook. I approach her as she snacks on the complimentary sunflower cookies and sips cedar maple tea. Elizabeth Brauer owns a new Finnish delicacies and design business called LUUMU. “The idea of really clean foods and back-to-basics is really appealing to me,” she says.

She’s had a lifelong interest in food. Recently, she harvested juniper berries and rose hips on Minnesota Point in Duluth. While living in Finland, she foraged wild berries, lingonberries, and blueberries. Her mother and grandmother garden; now that she has a more spacious apartment, she plans to do an indoor greenhouse.

I ask how accessible she feels the ingredients of the Sioux Chef cookbook are. She says she doesn’t hunt, and wouldn’t know where to buy rabbit. (Sherman gets his from DragSmith Farms, Hungry Turtle, and Eichten’s, all of them remote, and two in Wisconsin.)

While living in Finland, she got most of her protein from dairy and eggs. “It’s kind of a pain to cook for one person,” she admits. “It’s expensive.”

Not Ancient History

Back in Mahnomen, I tell Sherman I’m staying in town for lunch, and he grimaces and recommends driving south to Detroit Lakes.

In the name of research, I hit the Red Apple Cafe instead. The greasy spoon is the only lunch option on the rundown main street. The homes that surround it are derelict; many have boarded-up windows or appear to be abandoned post-fire. In the Red Apple Cafe’s windows, an autumnal display features ceramic bears in Native headdresses among fake leaves and pumpkins. Inside, it smells musty, like a grandparent’s basement; it’s just as cold, too, and no music plays.

And yet, it’s packed.

Construction workers in fluorescent hoodies hunch over the bar and stare into their smartphones. Elderly men at four-tops talk about the latest local pot bust. A pair of middle-aged male professionals discuss real estate and family life. After two thirty-something female customers depart following their soup and grilled cheese lunches (“Tell the cook to be generous on the cheese!”), I’m the only woman left, save for two employees.

The menu is what you’d expect of a small-town diner: mostly brown and beige foods. The "piece de resistance" is Tavern Mix: waffle fries, cheddar snaps, cream cheese jalapenos, mozzarella sticks, and battered mushrooms all piled atop French fries with the customer’s choice of two sauces for $8.50. (Cheese sauce is 80 cents extra.)

Before departing town, I stop at the Starmart gas station, also owned by the casino. In addition to the usual convenience store chips-and-drinks supply, it has a lunch counter dishing up Maple Pancake Stackers, Loaded Potato Pizzas, and Deluxe Philly Cheesesteaks. The store opens into Starmart Liquors, and as part of the Manitok Mall, all of this is ironically located next to Star Fitness, one of four fitness centers on the rez. There are a few bodies in motion inside.

Driving south, I can tell I’m getting closer to home as the eating options increase. The road is dotted with sun-bleached Perkins awnings, McDonald’s drive-thrus advertising EZ-OFF EZ-ON, strip-mall Subways, an abundance of Dairy Queens, and Holiday stations designed to look like log cabins.

I can’t help lingering on how much Sherman is up against in his quest to change America’s diet. What are the chances that people with little time, few means, and low motivation will forgo the convenience of processed and prepared foods?

“I’m not saying everybody has to be a jack of all trades,” he replies. “Some people love to farm, some people love to be outdoors and collect wild food, some people love to hunt, some people love to fish. It’s pulling all that back together—feeding off each other, literally.”

Sherman points out that these food systems aren’t ancient history. His great-grandfather grew up on the plains with traditional lifeways and ate indigenous foods. His grandparents were the first generation to be taken from their families, forced into boarding school, have their hair cut, and be stripped of their language and culture. “Basically, white-washed,” he says.

It seems ironic, then, that a large part of his audience is white.

“Some events in the cities will be mostly white, but it doesn’t matter,” he says. “We’re just sharing what we know how to do and we’re happy for anybody who wants to come and learn and listen. Whether you’re from Minnesota or Chicago or L.A., there’s indigenous history around you. And there’s so much we can learn from how those communities survived in those areas for so long.”

Originally published as a City Pages cover story in November

of 2017.