Andy is in a relationship. Make that several.

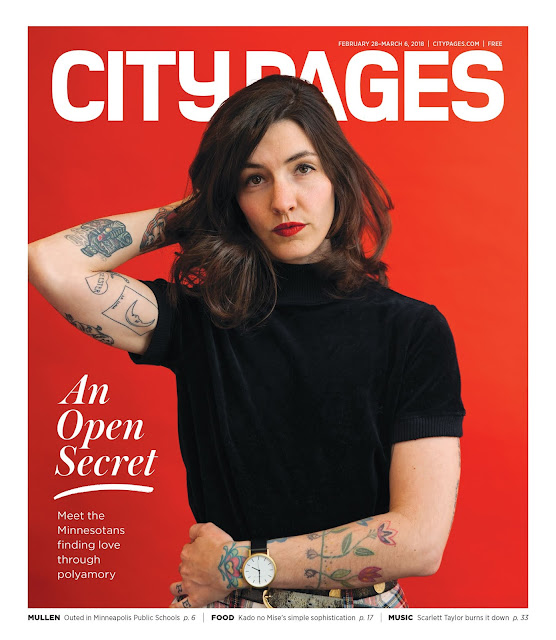

Over the past three years, the 31-year-old divorced mother with a ballerina’s physique, septum piercing, and “R-E-A-D M-O-R-E” inked on her knuckles has had three male partners—and subsequent heartbreaks.

She also dates a young married couple and occasionally sleeps with another married couple. Once, both married couples and Andy went camping together, children in tow.

She considers herself non-monogamous. Nationally, it’s estimated that 5 percent of the population has some sort of non-monogamous structure in their relationship. MN Poly, a St. Paul-based meetup group, boasts more than 1,200 members. Non-monogamy has recently caught on in pop culture, from onscreen interpretations in House of Cards, Insecure, and Professor Marston and the Wonder Women to advice columnist Dan Savage’s endorsement of “monogamish” relationships.

No two non-monogamous arrangements are exactly alike. People seek additional partners not just for sex but for affection, companionship, love, co-parenting, and socializing. These configurations require ongoing negotiations about appropriate partners, parameters of sex and dating, STD protection, and birth control.

Even the language non-monogamists use is carefully curated. Non-monogamy is an umbrella term; beneath it are myriad variations on the theme. Polyamory involves loving more than one person, with all the inherent emotional involvement and time investment. Sometimes polyamorous practitioners identify one partner as “primary,” creating a hierarchy to prioritize their many relationships.

Non-monogamy subtypes unfold from there. Open marriage allows one or both spouses to have sex with other people, often in a friends-with-benefits-style arrangement. Cuckolding is a fetish, one in which a husband takes pleasure in his wife sleeping with other men; voyeurism is often involved. Swinging is a limited-time opportunity for couples to have sex with other people; post-coital contact is discouraged. (Among non-monogamists, there’s a joke that goes: “Swingers have sex; polyamorous people have conversations.”) As for polygamy? It’s the black sheep of the non-monogamy family, weighted with religious, consent, and power structure issues.

That non-monogamy works for many doesn’t mean it’s accepted by the masses—it’s the status outsiders love to hate.

Controlled Chaos

If non-monogamy sounds complicated, it can be.

“It’s going to be messy. You have to allow for some

messiness,” Andy says.

“Messy” is a recurring theme in her relationships. A survivor of childhood sexual trauma and sexual assault, Andy met her ex-husband at 18. They married two years after their son’s birth—a decision Andy knew was doomed from the moment she walked down the aisle, sick to her stomach. Following a series of affairs, one of which turned violent, Andy moved out of her marital home. She immersed herself in therapy and joined a rape survivors support group, where she first saw the book The Ethical Slut (a.k.a. “the poly Bible”). She read it and wept at the realization that she could love more than one person at a time.

“Finding non-monogamy was like the stories I’ve heard of people finally realizing they’re gay,” she says.

All this time, she had been wrestling with the restraints of monogamy; now she saw a way to feel anything for anyone, as long as it was all out in the open.

But in practice, that level of transparency has been more elusive than she expected.

“I keep dating these people that have never really heard of, or tried, or read any poly literature,” Andy laments. “I have to coach, educate, counsel, and date them.”

In Andy’s experience, men will often present as single when in fact they’re still coupled, however tenuously. She says some men are willing to try non-monogamy for the first time but can’t hack the honesty required for the arrangement to work.

While there have been several failures on the boyfriend front, Andy is happily dating a married couple, the wife a fashionable bookworm, the husband a beer enthusiast. She sees the couple weekly and speaks to them daily.

“I fall in love with them more when I see them together because I watch how much they love each other and well they run their lives together,” Andy says. “They counsel me. They’re the emotional, strong, foundational support in my life.”

Three’s Company

Karen* and Jim* are a couple who share a suburban home with Karen’s bisexual partner Rob*, where all three parent four teenagers together. Karen and Jim didn’t plan on having a non-monogamous marriage per se, though Karen often joked that it would be nice to have a wife around to help with the child-rearing and housework.

Fate introduced the couple to Rob, a bearded teddy bear of a man, in 2011 while working on a Theater in the Round production. When Rob and Karen first met, he was six years divorced from the mother of his children. Karen appreciated Rob’s big energy and how easy it was to talk to him. Jim enjoyed his company, too; the three of them continued to work on theater productions together and became close friends. But Karen couldn’t kick the feeling that Rob was someone she needed in her life; the only other person she’d ever felt that way about was Jim.

“We always had a hard time saying goodbye at the end of the day. There was always more to talk about and it felt so good just to be together, even in a platonic, professional way,” Karen says of Rob.

“They clearly had a very close and compatible relationship,” Jim recalls. “We were all aware that sometimes people would see the two of them together and think they were acting ‘couplish’ and there would be various degrees of intrigue or scandal.”

Then tragedy struck. Rob’s 40-year-old ex-wife died suddenly of a brain aneurysm, thrusting Rob into the role of full-time caregiver to grieving children. He turned to Karen for support. The two families ended up moving in together and Karen came clean about her feelings for Rob. Three and a half years later, Karen maintains romantic relationships with both men.

“It’s not a fear of commitment. It’s commitment, plus one,” she says. “Jim and I spent 20 years together monogamously and this is not a plug to fill a problem. This is something that the parts are greater than the whole and it would be sad to not take advantage of this opportunity for everybody’s life to be fuller, richer, better.”

Sex is a part of, but not the epicenter, of their arrangement. “It’s not as racy a story as all that. It’s about driving kids to practice or who’s going to be home any given night of the week,” Karen says. “We don’t have specific designated anything. It’s catch-as-catch-can, but we try to make sure that there’s a balance and that nobody’s getting nothing.”

Change of Heart

For Lynn and Zach, a childless married couple, extramarital relationships are a way to expand their family. They also help Zach (who identifies as queer) better understand the clients at Zach’s private therapy practice, Sex from the Center.

For 50-year-old Lynn, all it took to convince her to try non-monogamy was a shoulder massage from a man at a party. As his hands kneaded her pale skin, she felt arousal stirring. It surprised her that she could feel such a thing in a way that didn’t detract from her love for her spouse of seven years, Zach. “It felt so separate and compartmentalized and like it cast no shadow [on my marriage],” Lynn recalls. “I had that sense of security and that sense of expansive love.”

Zach and Lynn’s relationship began in 2004 on Soulmatch, a Yahoo! personals dating site that no longer exists. Within six months of meeting, the couple got engaged and bought a house together. A Quaker wedding followed. Zach had never had an explicitly monogamous relationship before, but Lynn wasn’t interested in polyamory. In fact, her opinion on open marriage at the time was “no fucking way.” However, “I always had it in the back of my mind that if I felt really secure, I would consider it,” she says.

Then the shoulder massage happened. Around the same time, Zach’s therapy clients were exploring dating apps. To understand them better, Zach set up a profile. Lynn wanted one, too. Initially, they sought partners for affectionate touch only, but one thing led to another and soon they were each going on three to four dates per week with other people.

Zach currently has two girlfriends, relationships of four years and one year, respectively. “When Zach began seeing a new girlfriend, it added to the quality of our relationship,” Lynn says. “They could do things socially that I wasn’t interested in doing. Zach suddenly had a very rich social life, which I was so grateful for.”

In 2016, Lynn’s relationships with two steady boyfriends ended. Despite the emotional support of her husband, “I still had to go through all of that same heartache,” she says. She currently has “sexy fun” with a play partner once a month but they don’t keep in touch during the week, discuss their families, or do social activities together. She’s eager for more. “I’m ready to get back out there,” she says.

Tying the Knot

Lin (a stage name) and Howard*, both in their 30s and married for two years, have a pair of roommates: Lin’s ex-boyfriend and a bisexual woman who moved in two weeks after they started dating her. The couple also entertains a rotating cast of play partners that they meet in the kink community; in fact, they often act as each other’s wing-person.

“I love sitting down to a table with a group of friends and going, ‘Oh, I’ve slept with everybody here!’” says Lin, a 32-year-old with neon rainbow hair, retro glasses, and purple sparkly lipstick. Lin is blunt and occasionally she releases a laugh that seems to originate more from nerves than humor. She’s polite but with a cutthroat aura about her, like a cool, punk babysitter with a stern side.

The kink educator and photographer has identified as polyamorous her whole life. She met her husband, Howard, a 37-year-old straight man in IT, while he was in an open marriage. After four years of dating Lin, Howard divorced his wife. “It was pretty clear that we were a lot more compatible than they were,” Lin says. The couple married on New Year’s Eve of 2015, and in addition to their co-habiting partners, they date several others.

“It definitely keeps him entertained,” Lin says. “He loves exploring new people and coming back. For me, it satisfies that bisexual preference. I love women—I actually prefer women.”

Lin believes having multiple partners in no way diminishes the specialness of sex. “I think sex is always special,” she says. “It’s someone seeing you naked and communicating with someone about your wants/needs, and theirs. It’s just a warmer relationship with more people.”

The couple doesn’t invite just anyone into their bed, however. “When I okay somebody, I’ve probably known them for like five years,” Lin says. “Vetting is a big thing in the kink community and I use it for everything else, just making sure this person isn’t going to abuse anyone, isn’t going to cause any ridiculous drama, stuff like that.” Apparently, it’s been effective because she says she’s had “no major heartbreaks.”

In addition to her nonprofit office day job, Lin performs in A Stitch of Trouble, a rope-suspension and bondage performance duo. (She’s Stitch; her performance partner is Trouble.) “I tie people up and off the ground,” she explains. With wrists behind the back, ropes strung across the chest and intricately diamoned across the back, one can be suspended from a big ring and spun before an audience. Lin teaches these skills, sometimes known as “shibari,” at Open Minds Fusion Studio.

“People like it for a variety of reasons, including sex, dominance, and for the sheer aesthetics of it. It’s a challenge. It’s an art form,” she says. While Lin is no longer sexually involved with her live-in ex-boyfriend, they still do kink together. “I definitely can tie someone up and suspend them from the ceiling without it being sexual,” she says.

Lin and Howard currently have home-building plans that include movable hard-points (installed hardware that supports suspension from the ceiling) and 22-foot ceilings so she can practice rope work at home.

“The higher ceilings will allow us to develop and practice more complex acts,” Lin says, adding that the possibility for throwing more elaborate parties in the space will “definitely up the number of orgies I find myself in.”

Risky Business

Jealousy is the most common challenge in non-monogamous relationships, and it has multiple manifestations. For Lynn, it was particularly prevalent regarding one of Zach’s girlfriends. Lynn felt threatened by how sexy, smart, and fun to be around the girlfriend was. “She seemed to have a lot of power over Zach and Zach talked about her a lot... I always came to the same conclusion: ‘They’re just too happy!’ Then I would feel guilty for wanting to deny them happiness,” Lynn says.

Lynn has also struggled with comparing relationships and scorekeeping. “A situation of support and sharing their jubilance can very easily flip into jealousy,” she says.

While Andy believes jealousy is a social construct, that didn’t prevent her from experiencing it when the married couple she’s seeing purchased the same cut and color of panties for another woman during a four-month breakup with Andy. “I think I was thrown off by it because it felt as though they were replacing me with this new girl—just buying her the same stuff. Also, it made me feel as though the gift wasn’t as special to me because they just repeated it for this new woman,” Andy says, though she’s quick to add that moment seems laughable in hindsight. “I don’t know that I’d react in the same way if it happened again.”

Dishonesty and lack of transparency are other common hurdles. Lynn has communicated with several men who say they’re poly on the phone or online, but when they meet in person, the men admit their wives don’t know and request that she be “discreet” about their relationships. She’s also encountered “cowboys,” monogamous people who go along with the idea of non-monogamy in the hopes of wrangling non-monogamous partners into a monogamous relationship. Now she’s wary of starting a relationship with someone who has never considered or tried a non-monogamous relationship before.

STD prevention—or lack thereof—has been problematic for Andy. She contracted chlamydia from a boyfriend and had to alert the two married couples she’s been involved with to get tested. “Thank God none of them had gotten anything,” she says. “It’s annoying no matter when you get an STD, but you don’t want to disappoint people you love. Then they’re questioning your boundaries and their honesty.”

Both Andy and Lynn reported losing friendships over their lifestyles, in part because conversations surrounding non-monogamy can be upsetting for those who’ve been cheated on before, and don’t understand that non-monogamy and cheating are not one and the same.

More non-monogamy hitches: the clock and the calendar. “Remembering where you’re supposed to be, with whom, can be hard sometimes,” Lin says. Fitting everyone in can be rough, especially when there’s a new partner—and all that intoxicating infatuation energy—in the mix.

Balancing needs between multiple partners can be stressful, too. If a lover’s grandparent dies, for example, one may want to rush over to support them but already has plans with someone else. Or perhaps one’s partner was broken up with by someone else and now they’re not in the mood for a fun, lighthearted date.

Lynn occasionally feels like Zach is spread too thin. The couple experienced friction recently over the amount of communication between Zach and the newer girlfriend, whom Lynn says “does not feel like an enhancement. It feels like a distraction. It feels like instead of a whole husband, I have a third of a husband.” She quickly clarifies that this “isn’t the whole of how I feel about it. There are aspects of it that I heartily enjoy and appreciate and encourage, but there’s this little tinge of difficulty.”

For Lin, the biggest challenge in her arrangement has been a disability. She has lingering traumatic brain injury from a car accident, which causes her to sleep a lot and requires various medications and frequent doctors appointments. When she’s wiped out, the best her partners can hope for is to nap together.

Some of the stumbling blocks non-monogamous people face are downright mundane: delegating yard work, cat care, splitting bills. In other words, they’re doing much of the same relationship legwork as their monogamous counterparts.

One Foot in the Closet

Non-monogamy has yet to gain widespread acceptance in American society. Whispers circulate through the community about parents with litigious exes who might use one’s non-monogamous status to challenge custody rulings. Rumors of people who’ve lost jobs or have been shunned by their families abound. The people using pseudonyms in this article insisted on doing so because of fears of retaliation from family members or employers. Because of the judgment and shame surrounding non-monogamous arrangements, many practitioners choose to keep their relationships on the down-low.

Rob’s kids took the news of his unconventional arrangement with Karen and Jim in stride. Karen and Jim’s kids were wary; they needed assurance that Karen wasn’t cheating on, or hurting, their dad. Though all three adults consider themselves “out” to the theater community, it’s been an ongoing struggle to figure out how to be openly polyamorous among their families and friends, and in public.

“I don’t like feeling like we have to restrain ourselves from being normally affectionate so that people won’t talk,” Karen says, though she admits she behaves differently around people who do know and people who don’t.

“[Rob] is my partner. I feel like I need to talk about it. I can’t tell a story about my life that doesn’t include him at this point.” When they do disclose, they prefer to do so via instant messenger so people can have their reactions in private. So far, the ones who do know have not reacted negatively.

Lynn and Zach sent a letter out to family members early on explaining their arrangement just in case they were seen in public on dates with other people. The response was mostly silence. They have since distanced themselves from their families to avoid discussions or conflicts about their non-monogamous status. Lynn wishes that wasn’t the case. “I would like the right among my family to bring my other relationships to family gatherings,” she says. “But right now, it’s an ‘absolutely not’ situation.”

Lin says her family isn’t usually fazed by alternate forms of relationships, but when she disclosed her status to her mother via Facebook, her mother stopped talking to her for two weeks. Then, she called Lin and asked if Lin’s father touched her as a child. He hadn’t.

“Acceptance isn’t quite in her wheelhouse,” Lin says.

Lin’s father died when she was only 20 years old, but Lin says, “He would have loved hearing about my adventures in kink and polyamory.” Her in-laws still don’t know, though Lin wonders if they’ve figured it out and just haven’t addressed it yet. When it comes to co-workers at her day job at a local nonprofit, she keeps her status private.

Many of Andy’s family members, including her mother and step-father, do not know about her status, but her sister and some cousins are aware and accepting. She is also open at her teaching job, though a couple of older co-workers have made snide comments when she’s mentioned non-monogamy. “I just chalk that up to not being educated on it properly,” she says. Andy is especially vocal about her status to her @ladyroue Twitter followers. “If you don’t like me because of who I’m dating, because of this lifestyle, then you don’t need to be in my life,” she says. “Life is too short to not have my story told and to not be an inspiration for other people.”

Reflecting on her metamorphosis from adulterer to non-monogamist over the past four years, Andy says it’s changed how she views the world. She now runs a coaching practice called the Growth Arc to help others maneuver their relationships. Still, there’s something missing. “I’ve never had a primary partner, when they’ve wanted to pursue another relationship, do it ethically, with full knowledge and consent,” she says. “I feel sad, like, am I going to find someone that wants to be my primary partner?”

For non-monogamists, more is better—more love, more sex, more connection. But often with that comes more conflict, more heartbreak, more disappointment. The emotional toll non-monogamy can take on participants is immense—as are the rewards if the arrangement succeeds.

“This has the potential to be an exceptionally stable situation if the people are right,” says Karen. “It doesn’t work for everybody. I would never say that it is better than monogamy. I like monogamy. Monogamy is complicated enough. It really is. But when polyamory works, it can work beautifully.”

*Some names have been changed.

Originally published as a City Pages cover story in February

2018.