Charlie Parr is under siege.

His enemies: depression and suicidal thoughts. The roots musician has been battling these forces since his teens, but a resurgence over the past few years has tested his will to live.

Parr is no quitter. The lifelong Minnesotan has been making music for 42 years. He’s released 13 albums and built a fervent fan base at home and abroad, including seven tours in Australia and a dozen in Ireland. He played 272 road shows in 2016 alone. But his biggest achievement might be staying alive. That Parr is here, drinking coffee on a sunny Saturday afternoon at a hilltop farm-to-table restaurant in Duluth, is a testament to his endurance.

“It affects everything that I do, all day, every day—and all night,” the somber and soft-spoken musician says of the depression, which manifests in night terrors, blurry vision, clumsiness, an inability to concentrate, and a loss of interest in everything. In the midst of an episode, he avoids people and conversation. He feels anxious, fidgety, and distracted. He doesn’t want to listen to music, but silence isn’t any solace either. His clothes don’t fit right. His bed isn’t comfortable. He can’t play guitar with the staccato attack he’s known for.

“Depression’s really hard for me to describe because it doesn’t make any sense,” he says. “It’s like describing colors or music—you either have to listen to it or see it.”

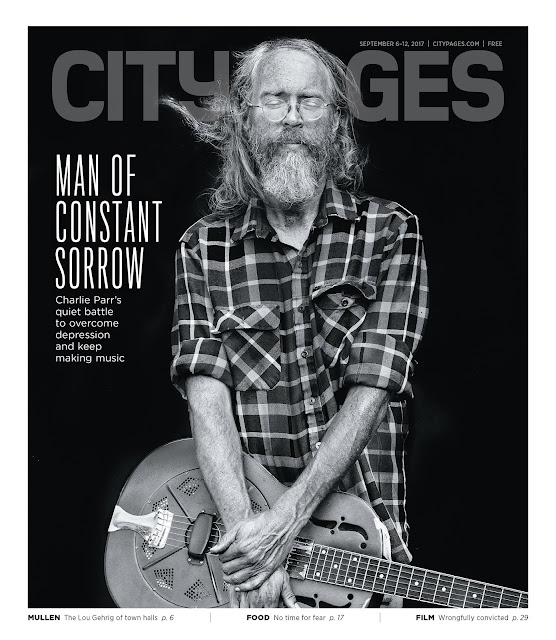

With his feral hair, peppery beard, and wide, wrinkled forehead, Parr appears weathered beyond his 50 years. A flannel shirt and blue jeans dangle from his wiry frame. Gold-rimmed glasses encircle kind blue eyes. The rare smile reveals a gap between his two front teeth.

Our server, who knows Parr by name, pours him cup after cup of black coffee. We’ve convened in a bookshelf-lined booth at the bustling Sara’s Table to talk about his 14th album, Dog, out September 8 on Red House Records. From the plucky, sparse “Sometimes I’m Alright” (Sometimes I’m alright / Another time it’s hard to tell / Like finding light / In the bottom of the darkest well) to the mournful “Salt Water” (Salt water, up to my door / There’s no one else home / I’m here all alone / Salt water under the eaves / There’s no relief / And I can’t leave), depression is all over this album.

Depression has haunted Parr for decades. He attempted suicide as a teen and was hospitalized four times between the ages of 13 and 15. After stints in long-term, lockdown psychiatric care, he had to face his peers, who met him with questions like: “Where were you?” “What happened to you?” “Are you crazy?”

Though his parents didn’t really understand what was happening to their son, “they made no judgment about it,” Parr says. “They did everything they could to help. It was a clean support, which I’m alive because of.”

But the current depression is unprecedented in intensity. In his youth, it came in waves and would eventually ebb. Now, he says, “It’s deeper. It feels more enduring.”

Parr was born in 1967 in Austin, Minnesota, to meatpacking parents who lived paycheck to paycheck. A latchkey kid, he got into his share of trouble. He tried to tunnel under the house and once doused his Lincoln Log town with lighter fluid and set it on fire.

Music was a constant presence in his home. His father had a “shambolic” record collection of old country, folk, and acoustic blues, while Parr’s sister exposed him to more contemporary music—the Beatles, the Grateful Dead. “I loved it all,” he says. “I listened to music all the time. I got into it really early.”

When Parr was 8 years old, his father bought him a guitar, and he became consumed with replicating songs by artists like Lightnin’ Hopkins and Woody Guthrie. He also frequented the Austin public library, which housed what he calls “the biggest collection of odd folk records,” where he checked out Harry Smith’s Anthology of American Folk Music and albums by Charley Patton, then tried to learn the tunes by ear. While he had friends, Parr felt lonely in his passion for music of a different era. “I had no problem with dropping everything and riding my bike home and playing the guitar,” he says.

In ninth grade, Parr started skipping school and got into “stupid things” like drinking and cars. He even ended up in jail. (“It’s easy to get picked up if you walk down the street intoxicated and pee on something—suddenly you’re in jail.”) Graduating high school was not among his priorities. “I figured I didn’t have much to offer, so there was no point in trying,” he says. He dropped out and assumed he’d always be a drifter.

But at a therapist’s urging, he began studying for his GED during night shifts at a filling station, and he scored unexpectedly high on the test. “My ego brain kicked in and I thought, ‘I should go to college. I could easily be the next Friedrich Nietzsche.’”

So Parr moved to the West Bank in Minneapolis, where he enrolled in—and dropped out of—classes at a variety of colleges, eventually earning a B.A. in philosophy from Augsburg College in 1992.

“Instead of doing something smart, like getting some kind of trade, I did the stupidest thing and took liberal arts classes for philosophy, which, I think, helped me in a personal way, but I was unemployable when I was 20,” he says. “I had no self-discipline. I still don’t. I’m not a multitasker. I’m very much a unitasker. I can do one thing, I get obsessed with that one thing, and that’s what I want to do.”

Parr moved to a rooming house behind the Mixed Blood Theatre, and found himself right around the corner from people playing the music he had listened to all his life. On Thursdays, he walked downtown to see Dave Ray or Tony Glover at the Times Bar. On Fridays, he’d cram into the 400 Bar for Willie Murphy. On Saturdays, he’d haunt the Riverside Cafe. On Sundays, he’d hit the Viking Bar, where Spider John Koerner played. “I’d take it all in, then go home and try to play,” Parr says.

After working a series of menial jobs, Parr finally found meaningful employment in 1992 as an outreach worker for the Salvation Army. He befriended homeless people on the street and provided basic needs: a pair of socks, a blanket, a cup of coffee, a hot meal, a friendly conversation.

“I loved talking to them,” Parr says. “They were super, super smart. They were incredibly resilient, inventive people, fascinating people—musicians, thinkers, readers—who had fallen accidentally into these horrible times and then become enmeshed in this ball of crap.”

Though Parr adored outreach, he didn’t have the ambition to climb the social services career ladder. Paperwork and conferences were not his strong suits. “I loved the act of giving food to someone who was hungry, but I didn’t have the talent to do anything more than that,” he says.

Parr met fellow musician Mikkel Beckmen while making sandwiches for his clients at a shelter, and they discussed joining forces as a Bukka White and Wash-board Sam-style duo. One day, passing the Steeple People thrift store on Lyndale, Parr saw a $12 washboard hanging in the window. He bought it for Beckmen and they’ve been playing together ever since.

“A songwriter is a nosy person in some ways, someone who’s curious about the human condition,” Beckmen says of Parr. “You get the sense that he’s genuinely interested in you and genuinely appreciative in having met you. I think that comes across as well as genuine curiosity and continued wonderment at all parts of life, whether they’re the tough parts or the sorrowful parts or the challenging parts, but also the quirky, small things that happen in a day that are so interesting or fascinating.”

“Songwriting, to me, before 1995 was a mysterious thing,” Parr says. “I thought, ‘How do you even do that? I can’t even write a poem. I’m not a writer. I’m just a dude, just a loser, walking around.’”

That all changed after Parr’s father died from lung cancer. “He went from being this robust, big, muscular dude to being tiny,” he says, the sadness still audible in his voice. “It was a grinding, horrible process, six months maybe, from the time we found out to the time that he died.”

Parr turned to songwriting to deal with that loss. “It affected me in this really visceral, terrifying way,” he says. “Song-writing, for me, got connected to grief and pain. There’s no point writing about happy things.”

Parr drew his earliest lyrics from the stories his father had told him of his life; his melodies were inspired by the music his father had exposed him to. “So I’m writing songs from the perspective of 1931, which came out completely different than the people I was around who were writing more contemporary-sounding songs because they were listening to more contemporary music,” he says. Little did he know how popular his anachronistic style, this sonic relic reborn, would become.

“[My father] just wanted me to do the thing that moved my heart the most, which is what I’m doing, and he never got to see it.”

In 1999, seeking a lower cost of living, Parr moved to Duluth. As he had in Minneapolis, he worked with the homeless and played weekly gigs around town. “I didn’t have the fire to do much more than that,” he says. In 2001, at the behest of Mark Lindquist, founder of Shaky Ray Records, Parr recorded his first album, Criminals and Sinners, in Lindquist’s basement studio.

Alan Sparhawk of Low got word of the album and went to see Parr play at Fitger’s Brewhouse in Duluth. “The music he was laying out for the dozens of dancing revelers was immediate, primal, and soulful,” Sparhawk says. “I could tell he had spent the time to really become the music. Only time spent makes that happen. Only real love and devotion.”

The two musicians became fast friends, and the following year, Sparhawk asked Parr to open for the Black-Eyed Snakes on tour in the British Isles. The tour concluded two weeks later. “They left me off in London in Kings Cross,” Parr recalls. “Not really understanding how big London was, I walked to the venue where I was supposed to play that night.

It took me most of the entire day. I must have looked like an idiot. I had a guitar strapped to my back and a backpack over my shoulder and I had my little Let’s Go London book.”

Back in Duluth, opportunities to play continually arose for Parr, and he hasn’t held a day job since. But even musicians have occupational hazards. In 2006, Parr was diagnosed with focal dystonia, a neurological condition that hampered his ability to play the guitar. “It’s like repetitive stress syndrome for your brain. There’s nothing you can do. There’s no pill. There’s no surgery,” he says.

The specialist he consulted recommended that Parr give up the guitar for six months to a year. That wasn’t an option for someone who considers music his “life support.” Instead, Parr altered his picking style, relying on his thumb and pointer finger. “It’s like you have a ham instead of a hand and you’re just slapping stuff with it,” he says of his “deformity.”

The diagnosis was a wake-up call. Parr realized his lifestyle up until then had been “irresponsible.” Inspired in part by friend and engineer Tom Herbers’ success with defeating depression through meditation, yoga, and diet, Parr went vegan and cut back on drinking. Within two weeks, he felt “weirdly good.”

Parr now tours with a cooler and collects leftover food from the venues he plays in. He wraps the grub up in tortillas and tinfoil and heats it on the engine of his van while driving to the next stop. It’s just one of the ways he saves money on tour. His van is outfitted with a bed in the back. He can—and does—sleep anywhere, from rest stops to state parks.

It’s raining in Minneapolis, and Parr’s sold-out show at the Mill City Museum has been moved indoors beneath a grain-themed ceiling. The air is stagnant and thick with the aroma of fried food. Dressed in a well-worn T-shirt and baggy jeans, Parr squints at the floor from his seat onstage. “This is the very first time I’ve written a set list in my life,” he says into the mic. It’s a courtesy for his bassist, Liz Draper, with whom he’s never played as a duo before. Parr doesn’t exactly stick to it, but Draper keeps up.

“With Charlie, it’s kind of all a blur,” she tells me later. Parr’s off-the-cuff style “sure keeps it interesting,” she says. “I don’t want to say it makes it hard, but it definitely keeps you on your toes.”

Parr folds his body over the guitar and launches into “HoBo” with lightning-fast fingers and a surgeon’s concentration. His cricket-like legs jitter up and down as he sings:

Won’t somebody tell me what I’m doing here?

Won’t somebody tell me where I’m going?

Won’t somebody spend a blank minute on me?

Pray for a hobo who’s gone wrong

Flannel and beards abound among the audience members. They range from 20-something hipsters to gray-haired baby boomers, and with polite Minnesotan restraint, they absorb the music attentively, tap their sneakered and sandaled feet to the beat, and occasionally add a shoulder sway.

Between songs, Parr inspires laughs with his deadpan humor. “This is a folk song. It’s terrifying and sad,” he warns before break-ing into “Old Dog Blue.” As comfortable as if he were shooting the shit with an old friend at his kitchen table, he shares stories from his family life: the horrified reaction when his son, a Thomas the Tank Engine fan, saw a real train for the first time (“It has no face!”) and how his dog was “acting” in a production of Legally Blonde.

Parr tells the audience he hasn’t been home in five weeks. “Time no longer exists,” he says. “I’m in a crazy place right now.” He recounts his West Coast travels, from visit-ing Watts Tower in Los Angeles to sleeping beside Devils Tower in Wyoming. He shares how a Canadian border agent confiscated an apple and an avocado from him.

For two hours, Parr plays tirelessly, switching between a Resonator and a 12-string guitar while Draper alternates between upright and electric basses. When the crowd is sufficiently liquored up, a couple kisses and intermittent whoots erupt, and a request for “Badger” echoes through the room.

At intermission, fans line up, eager to chat and get their records autographed. A pair of young men with flat sheaths of waist-length hair return to their seats alight, blowing on the spots where Parr scrawled his name across their records. “I always make sure to tell people, ‘Writing on the records diminishes their resale value.’ But they still want it,” he says. When I suggest he’s humble, he denies it. “I’m pretty egotistical. I believe I belong onstage,” he says. “To be a musician, you have to have a pretty healthy ego because you are putting stuff out into the world that is so personal.”

To see Parr on stage, you’d never realize how relentlessly depression stalks him. But at times it even overtakes him on tour, and he’s got a tricky choice: disclose what he struggles with or fudge the truth. “The promoter’s there and she has a smile on her face and she’s happy to see you and you can’t function. And it’s hard to say what it is that’s happening,” he explains.

“Sometimes people—well-meaning people—really want to help you. They give you suggestions and it’s fine, it’s nice, but depression isn’t sadness. It’s not a lack of happiness. It’s a thing. It’d be easier to say, ‘I have the flu today.’”

The flu is too gentle a metaphor. Depression is more like cancer: formidable, insidious, and life-threatening. And depression isn’t the worst of it—the suicidal urge is. “I don’t hate much, but that impulse I hate,” he says. “It comes out of nowhere. It feels like when you’re really weak, that thing shows up and you feel very unstable and unsafe.”

At those times, he feels camaraderie with the depression. “Depression and I are trying to survive. Suicide doesn’t want that,” he says. When self-harm entices him, he uses distraction. He has outsmarted suicide by locking himself out of his van and exiting rooms when open windows tempted him. “It’s all you can do to run away from it,” he says. “It’s fight or flight.And it’s that serious.”

Parr’s life is hardly devoid of pleasure. He’s grateful that he gets to play the guitar every day, do shows, take walks, ride his bike, parent his 10-year-old daughter and 16-year-old son, of whom he says he is “a massive fan.” He uses tools like mindfulness, exercise, and diet to mitigate the depression. While he has never been “med compliant,” he does therapy sporadically.

And of course, he makes music. Though depression forced Parr to cancel three recording sessions of Dog, the album is finally finding its way to listeners. Playing the songs before audiences has already proved cathartic. Despite the tunes’ grim roots, “they don’t mean what they did any-more. They’ve already morphed,” he says. While the lyrics are heavy, the music isn’t resigned; there’s a momentum to his picking style that evokes perseverance.

“On this album, he has come up against— like we all do—the fact that we are creatures who are part of time and that time runs out eventually,” Beckmen says. “We age, we get older, we have experiences, things happen to us that become a part of who we are. There’s a profound sense that sometimes life can get very scary, very sorrowful, and yet, there’s a way out, a way forward.”

Parr himself seems more concerned with finding the way forward than the way out— he considers his depression permanent. And so, though he was hesitant to make his battle with depression public, he felt the need to unburden himself of his secret. “I don’t want to live a disingenuous life,” he says. “I want to live a life where I’m not ashamed.”

Depression, Parr says, has added a “weird note of depth and

meaning” to his life. “I’ve been blessed with continual life-changing

experiences every day.” Reflecting on our conversation, he adds, “Maybe this will

be one of them.”

Originally published as a City Pages cover story in September of 2017.